Economic Growth and the Role of Human Capital

PUBLISHED:

Measuring economic growth allows us to determine whether an economy is expanding, remaining unchanged, or declining. Assessing economic performance, namely economic growth expressed through Gross Domestic Product (GDP), is a common method for evaluating the overall health of an economy. A healthy economy generates jobs and tends to lead to improvements in per capita income and living standards.

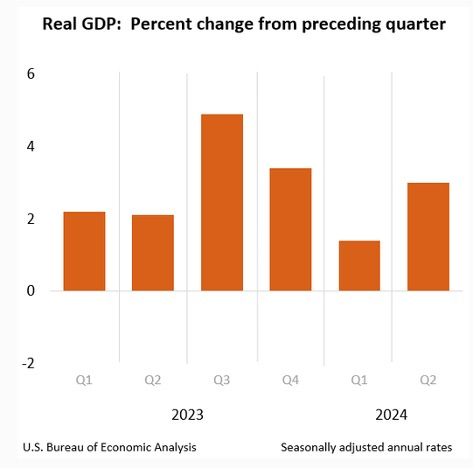

In spite of the COVID-19 pandemic’s adverse effects on productivity, supply chains, and economic output worldwide, the U.S. economy has recovered relatively well during the past couple of years. In 2023, the U.S. economy grew at an average rate of 2.5 percent, indicating modest growth. Although there were some fears of economic decline (and trepidation concerning a potential recession), the U.S. economy has rebounded and created jobs, raising overall economic output. The figure below shows the percent change in real GDP (adjusted for inflation) in the United States during the past six quarters. As we can observe, throughout this time period, the U.S. economy has had positive economic growth.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis

Meanwhile, some countries such as Mexico and India have struggled economically, particularly on a GDP per capita basis. So, one might wonder, why has the U.S. economy been able to recover notwithstanding the difficulties of the COVID-19 pandemic? What has enabled the U.S. to remain economically resilient during these past few years? We will explore this a bit later. But first, let’s discuss how the theories behind economic growth have evolved over time.

Background on the Study of Economic Growth

Economic growth has been studied for several decades. The economist, Robert Solow, became a prominent scholar on the subject in the 1950s. Solow’s theories proposed the role of accumulation of physical capital and emphasized the importance of technological progress as the ultimate driving force behind sustained economic growth.

Growth theorists in the 1950s argued that technological progress occurred in an unexplained manner, and thus they placed technological growth outside of their economic model. However, there was a significant shortcoming in assuming that long-run economic growth is largely determined by some unexplained rate of technological progress which, after all, could not be modeled.

By the 1960s, growth theory was based mainly on the neoclassical model, developed by Ramsey (1928), Solow (1956), and Koopmans (1965), to name a few. The neoclassical model considered individual consumers and firms and assumed that they make rational choices to maximize their utility or profits, and it also presumed perfect information and zero transaction costs. The neoclassical growth model posited that economic growth results from capital accumulation through household savings. Over time, economists would realize that consumers and decision makers in general are not always rational, markets indeed lack perfect information, and transactions between parties certainly yield costs.

In the 1980s, most of the research conducted by economists centered on “endogenous growth” theories, in which the long–term economic growth rate was largely assumed to be determined by government policies. As such, economists argued that government policies help to motivate businesses to invest in research and development so they can continue to drive innovation. Several of the economic models that emerged also began to broaden the definition of capital, and included references to human capital (Lucas 1988; Rebelo 1991; Romer 1986). Moreover, another key assumption of the endogenous growth theory is that economic growth is principally the result of internal forces, rather than external ones.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, scholarly works began to posit that technological progress generated by the discovery of new ideas was the only way to avoid diminishing returns in the long run. Two professors from the University of Chicago, Paul Romer and Robert Lucas, introduced the notion of “ideas” and of “human capital” as variables that have influence on economic growth. From their research emerged the subfield – the economics of technology. In their ensuing models, the purposive behavior that underlay innovations hinged on the prospect of monopoly profits, which provided individual incentives to carry out costly research (Aghion and Hewitt 1992; Grossman and Helpman 1991; Romer 1990).

Economists’ earlier theories about economic growth had suggested that labor and physical capital and increased productivity from technology are the primary factors that contribute towards economic growth. Over time, however, economists recognized the challenges of achieving economic growth especially as there are diminishing returns to capital and labor, combined with the reality that some countries are not as efficient in their allocation of resources as suggested by the neoclassical growth model. Consequently, Robert Lucas (1988) and Paul Romer (1994) as well as others (Barro 1997; Rebelo 1991; Sachs and Warner 1997) proceeded to advance ‘Endogenous Growth Theory’ by arguing that economic growth can be driven by human capital, namely by the expansion of skills and knowledge that make workers productive. Thus, they argued that human capital has increasing returns to scale (i.e., the output increases by a larger proportion than the increase in inputs).

The Influence of Human Capital on the Economy

For some time now, there has been growing research on the impact of human capital on the economy. A study conducted by the Centre for Economics and Business Research in 2016 indicated that human capital is nearly 2.5 times more valuable to the economy than physical assets such as technology, real estate and inventory. The study also highlighted that for every $1 invested in human capital, $11.39 is added to GDP (CEBR, 2016). This study underscored the important role human capital plays in driving economic growth. When human capital increases in a society, including in areas such as education, science, manufacturing, and management, it leads to increases in innovation, increased productivity, and improved rates of labor force participation, all of which support economic growth.

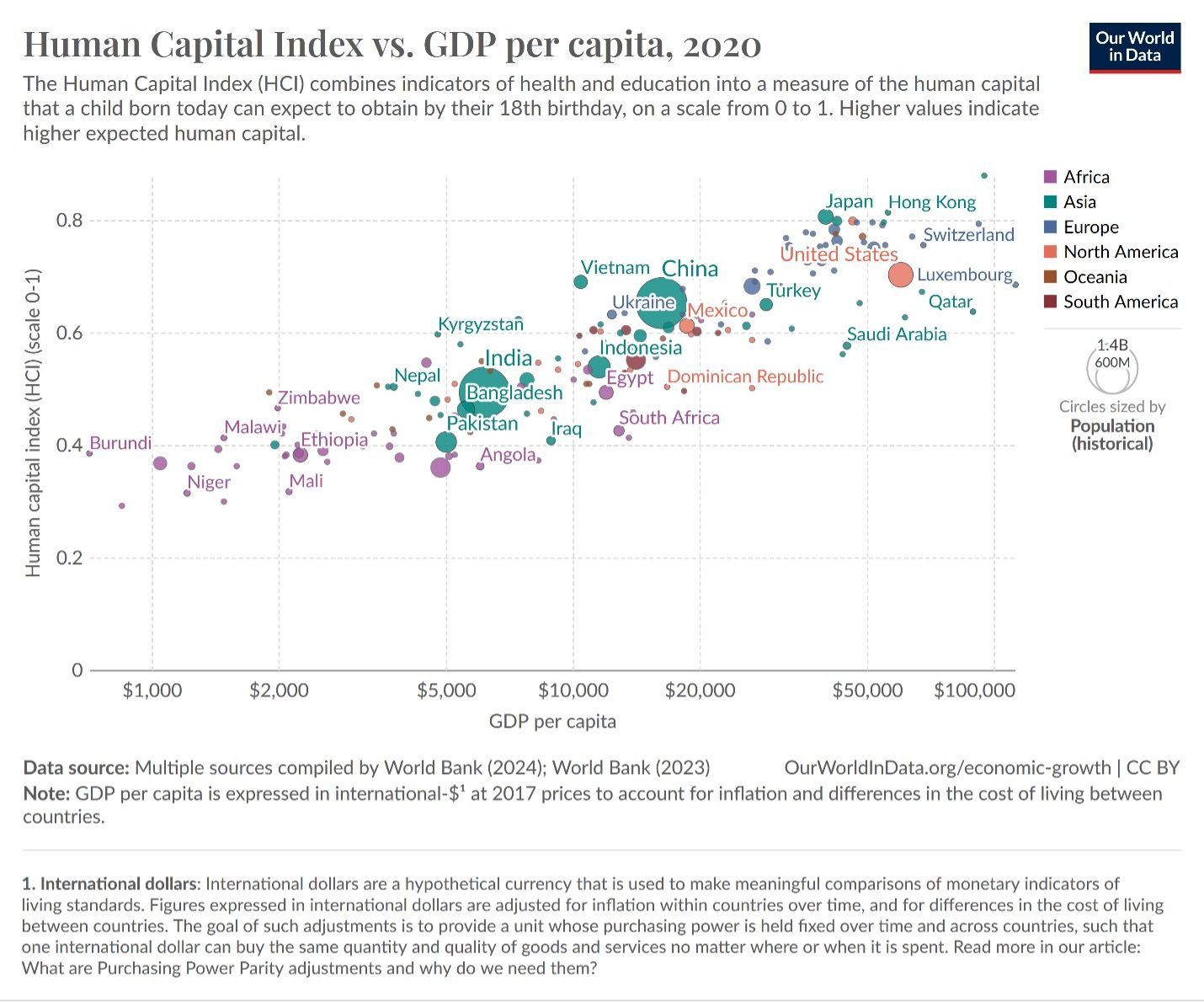

And so, we come back to the questions: Why has the U.S. economy been able to recover notwithstanding the difficulties of the pandemic? What has enabled the U.S. to remain economically resilient during these past few years? I argue that the United States has been able to withstand the adverse effects of the pandemic due to its sizable stock of human capital. Since the U.S. is a high-income country with a workforce that has relatively high levels of education and health (on average), it tends to develop human capital at a higher rate (relative to other countries), enabling it to contend with economic adversity through innovation driven by knowledge workers. Below is a graph using data from the World Bank which shows the relationship between the Human Capital Index (Note: HCI is comprised of education and health components), and GDP per capita. As we can see from the graph, the United States has a high HCI score (0.7) and a high level of GDP per capita (slightly above USD$60,000).

Source: Our World in Data, 2024

Key Lessons

The Human Capital Index, developed by the World Bank, conveys the productivity of the next generation of workers compared to a benchmark of complete education and full health (World Bank, 2024). The HCI measures the knowledge, skills, and health that a child can expect to accumulate during their youth, taking into account factors such as education, health, and survival rates. The index is devised to indicate how improvements in health and education outcomes can lead to considerably greater productivity of the next generation of workers. Higher values indicate higher expected human capital. The United States’ relatively high HCI index score of 0.7 as of the year 2020, indicates that the country had made investments in human capital. A country's HCI score is its distance to the “frontier” of complete education and full health. Based on this index score, a child born in the United States will be 70 percent as productive when she grows up as she could be if she enjoyed complete education and full health. In other words, the future earnings potential of children born will be 70% of what they could have been with complete education and full health.

Unlike physical capital, human capital has increasing rates of return. Therefore, economic growth is augmented at a larger rate as human capital accumulates (people acquire more knowledge and skills). If human capital is indeed nearly 2.5 times more valuable to the economy than physical assets, then economies (nations) ought to invest in those areas that support human capital, namely education and health. And if investing $1 in human capital yields an estimated $11.39 to GDP, then countries will benefit greatly from investing in improving the health and education of people.

Nations that invest in human capital are more adept at developing innovations that improve efficiency, competitiveness, and productivity. Human capital is also a key input in the research sector, which develops and incubates new ideas that support technological progress and innovation. Moreover, investing in education is intricately connected with the development of human capital and economic development (Barro and Lee 1993; Romer 1993). Hence, an increase in the educational attainment level of the population will, in turn, yield knowledge spillover effects which spur innovation across different industries and sectors. And at the aggregate level, innovation will produce the long-term effect of increasing the economic growth rate.

Innovation led by human capital (skilled knowledge workers) provides productivity gains that allow firms to expand their size, market reach and profits. Human capital also contributes to the efficiency and effectiveness of organizations within the social and public sectors. In all, investing in human capital is beneficial to the well-being of the economy and society in general. Enhancing the education and health of people is essential to developing human capital and economic resilience. The acquisition of skills and knowledge enable ‘knowledge workers’ to drive entrepreneurial activities and innovation, proving that human capital is indeed the most important factor to developing a resilient economy and a functioning society.

References

Aghion, P. and P. Howitt (1992). A Model of Growth through Creative Destruction. Econometrica, 60, 323-351.

Barro, R. (1997). Determinants of economic growth: a cross-country empirical study (2nd ed.). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Barro, R. J., & Lee, J. W. (1993). International comparisons of educational attainment. Journal of monetary economics, 32(3), 363-394.

Centre for Economics and Business Research. (2016). Korn Ferry Economic Analysis: Human Capital.

Data Page: Human Capital Index. Our World in Data (2024). Data adapted from World Bank. Retrieved from https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/human-capital-index-in-2020 [online resource]

Grossman, G. M. and E. Helpman (1991). Innovation and Growth in the Global Economy. The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Koopmans, T.C. (1965). On the Concept of Optimal Economic Growth. In: Johansen, J., Ed., The Econometric Approach to Development Planning, North Holland, Amsterdam.

Lucas, R. E. (1988). On the mechanics of economic development. Journal of Monetary Economics, 2, 3-42.

Ramsey, F.P. (1928). A Mathematical Theory of Saving. Economic Journal, 38, 543-559.

Rebelo, S. (1991). Long-run policy analysis and long-run growth. Journal of Political Economy. IC, 500-521.

Romer, P. M. (1986). Increasing Returns and Long-run Growth, Journal of Political Economy, University of Chicago Press, vol. 94(5), pages 1002-1037, October.

Romer, P. M. (1990). Endogenous Growth and Technical Change, Journal of Political Economy, 99, pp. 807-827.

Romer, P. M. (1993). Idea gaps and object gaps in economic development. Journal of Monetary Economics, 32(3), 543-573.

Romer, P. M. (1994). The origins of endogenous growth. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 3-22.

Sachs, J. D., & Warner, A. M. (1997). Fundamental sources of long-run growth. The American Economic Review, 184-188.

Solow, R. M. (1956). A Contribution to the Theory of Economic Growth, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, President and Fellows of Harvard College, vol. 70(1), pages 65-94.

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. (2024). Gross Domestic Product. Retrieved from: https://www.bea.gov/data/gdp/gross-domestic-product [online resource]

World Bank. (2024) World Bank Group launches Human Capital Index (HCI). Retrieved from: https://timeline.worldbank.org/en/timeline/eventdetail/3336 [online resource]