From a Functional to a Free Society-- The End of Economic Man: Drucker's Diagnosis of Totalitarianism

PUBLISHED:

Peter Drucker suggested that readers view his first three books as a unified body of work: The End of Economic Man(1939), The Future of Industrial Man (1942), and Concept of the Corporation (1946). These works share a common theme: politics. Drucker did not think about politics like scholars who strictly follow modern social science norms. Instead, he viewed politics as part of social ecology and understood political events through the dynamic changes in social ecology.

Despite having "corporation" in its title and using General Motors as a case study, Concept of the Corporation is indeed a book about politics. In this work, Drucker attempts to address the main issues that industrial society must resolve: the legitimacy of managerial authority, the status and function of managers and workers, and the power structure of society and organizations. In Drucker's own words, this is a book exploring the specific principles of industrial society. Corresponding to these specific social principles, Drucker had earlier attempted to develop a general social theory, which was the aim of The End of Economic Man and The Future of Industrial Man.

The subtitle of The End of Economic Man is "The Origins of Totalitarianism." The book focuses on how society disintegrates in industrial societies and how totalitarianism rises. For Drucker, the real challenge of this topic isn't explaining how Hitler and Mussolini came to power, nor the actions of Germany and Italy in government, military, and economic spheres. Rather, it's understanding why some Europeans accepted clearly absurd totalitarian ideologies, and why others seemed potentially receptive to them.

Drucker's writing style is argumentative. He clearly knew that to effectively advance his arguments, he needed to engage with popular theories of his time. Back then, there were two main explanatory approaches to Nazism and Fascism, which Drucker termed "illusions." Some viewed totalitarianism as ordinary political turmoil similar to previous historical revolutions. In their view, totalitarianism was characterized merely by cruelty, disruption of order, propaganda, and manipulation. Others considered totalitarianism a phenomenon unique to Germany and Italy, related to their specific national characters.

Drucker thoroughly refuted explanations based on "national character." He believed that any historical approach appealing to "national character" was pseudo-history. Such theories always emphasize that certain events were inevitable in certain places. But all claims of "inevitability" negate human free will and thus deny politics: without human choice, there is no politics. If the rise of totalitarianism were inevitable, there would be no need or possibility to oppose it.

Viewing totalitarianism as an ordinary revolution is equally dangerous. This thinking merely emphasizes how bad Nazis and Fascists were. But the real issue is that Europeans were not merely submitting out of fear—they were actually attracted to totalitarianism. And those attracted weren't just the ignorant masses but also well-educated intellectual elites, especially the younger generation. The world cannot defeat totalitarianism through contempt alone, especially if that contempt stems from ignorance. Understanding the enemy is a prerequisite to defeating it.

Drucker identified three main characteristics of Nazism and Fascism (totalitarianism is a social type, with Nazism and Fascism being its representatives in industrialized Europe):

1. The complete rejection of freedom and equality, which are the core beliefs of European civilization, without offering any positive alternative beliefs.

2. The complete rejection of the promise of legitimate power. Power must have legitimacy—this is a long-standing tradition in European politics. For power to have legitimacy means that it makes a commitment to the fundamental beliefs of civilization. Totalitarianism denied all European beliefs, thereby liberating power from the burden of responsibility.

3. The discovery and exploitation of mass psychology: in times of absolute despair, the more absurd something is, the more people are willing to believe it.

The End of Economic Man develops a diagnosis of totalitarianism around these three characteristics. Drucker offers a deeper insight: totalitarianism is actually a solution to many chronic problems in industrial society. At a time when European industrial society was on the verge of collapse, totalitarians at least identified the problems and offered some solutions. This is why they possessed such magical appeal.

Why did totalitarianism completely reject the basic beliefs of European civilization? Drucker's answer: neither traditional capitalism nor Marxist socialism could fulfill their promises of freedom and equality. "Economic Man" in Drucker's book has a different meaning than in Adam Smith's work. "Economic Man" refers to people living in capitalist or socialist societies who believe that through economic progress, a free and equal world would "automatically" emerge. The reality was that capitalism's economic freedom exacerbated social inequality, while socialism not only failed to eliminate inequality but created an even more rigid privileged class. Since neither capitalism nor socialism could "automatically" realize freedom and equality, Europeans lost faith in both systems. Simultaneously, they lost faith in freedom and equality themselves. Throughout European history, people sought freedom and equality in different social domains. In the 19th century, people projected their pursuit of freedom and equality onto the economic sphere. The industrial realities of the 20th century, along with the Great Depression and war, shattered these hopes. People didn't know where else to look for freedom and equality. The emerging totalitarianism offered a subversive answer: freedom and equality aren't worth pursuing; race and the leader are the true beliefs.

Why did totalitarianism reject the promise of power legitimacy? One reason was that political power abandoned its responsibility to European core beliefs. Another reason came from the new realities of industrial society. Drucker held a lifelong view: the key distinction between industrial society and 19th-century commercial society was the separation of ownership and management. The role of capitalists was no longer important. Those who truly dominated the social industrial sphere were corporate managers and executives. These people effectively held decisive power but had not gained political and social status matching their power. When a class's power and political status don't match, it doesn't know how to properly use its power. Drucker believed this was a problem all industrial societies must solve. Totalitarianism keenly perceived this issue. The Nazis maintained property rights for business owners but brought the management of factories and companies under government control. This way, social power and political power became unified. This unified power was no longer restricted or regulated—it became the rule itself.

Why could totalitarianism make the masses believe absurd things? Because Europeans had nothing left to believe in. Each individual can only understand society and their own life when they have status and function. Those thrown out of normal life by the Great Depression and war lost their status and function. For them, society was a desperate dark jungle. Even those who temporarily kept their jobs didn't know the meaning of their current life. The Nazi system could provide a sense of meaning in this vacuum of meaning—though false, it was timely. Using the wartime economic system, the Nazis created stable employment in a short time. In the Nazi industrial system, both business owners and workers were exploited. But outside the industrial production system, Nazis created various revolutionary organizations and movements. In those organizations and movements, poor workers became leaders, while business owners and professors became servants. In the hysterical revolutionary fervor, people regained status and function. Economic interests were no longer important, freedom and equality were no longer important; being involved in the revolution (status) and dying for it (function) became life's meaning. The Nazis replaced the calm and shrewd "Economic Man" with the hysterical "Heroic Man." Though absurd, this new concept of humanity had appeal. What people needed was not rationality but a sense of meaning that could temporarily fill the void.

Those theorists who despised totalitarianism only emphasized its evil. Drucker, however, emphasized its appeal. He viewed totalitarianism as one solution to the crisis of industrial society. From 19th-century commercial society to 20th-century industrial society, the reality of society changed dramatically. 19th-century ideas, institutions, and habits could not solve 20th-century problems. Capitalism could not fulfill its promises about freedom and equality, and neither could Marxism. It was at this point that totalitarianism emerged. Nazism and Fascism attempted to build a new society in a way completely different from European civilization. Drucker said the real danger was not that they couldn't succeed, but that they almost did. They addressed the relationship between political power and social power, proposed alternative beliefs to freedom and equality (though only negative ones), and on this basis provided social members with new status and function.

The war against totalitarianism cannot be waged merely through contempt. Defeating totalitarianism is not just a battlefield matter. Those who hate totalitarianism and love freedom must find better solutions than totalitarianism to build a normally functioning and free industrial society.

Totalitarianism gave wrong and evil answers. But they at least asked the right questions. Industrial society must address several issues: the legitimacy of power (government power and social power), individual status and function, and society's basic beliefs. These issues became the fundamental threads in Drucker's exploration of industrial society reconstruction in The Future of Industrial Man.

The Future of Industrial Man: From Totalitarian Diagnosis to General Social Theory

Both The End of Economic Man and The Future of Industrial Man feature the prose style of 19th-century historians. Even today, readers can appreciate the author's profound historical knowledge and wise historical commentary. For today's readers, the real challenge of these two books lies in Drucker's theoretical interests. He doesn't simply narrate history but organizes and explains historical facts using his unique beliefs and methods.

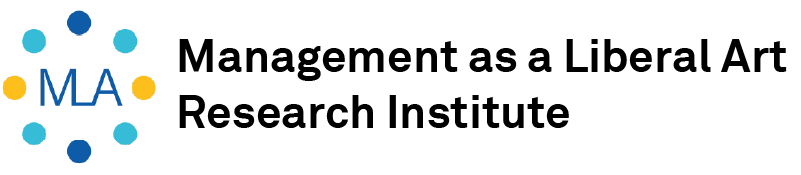

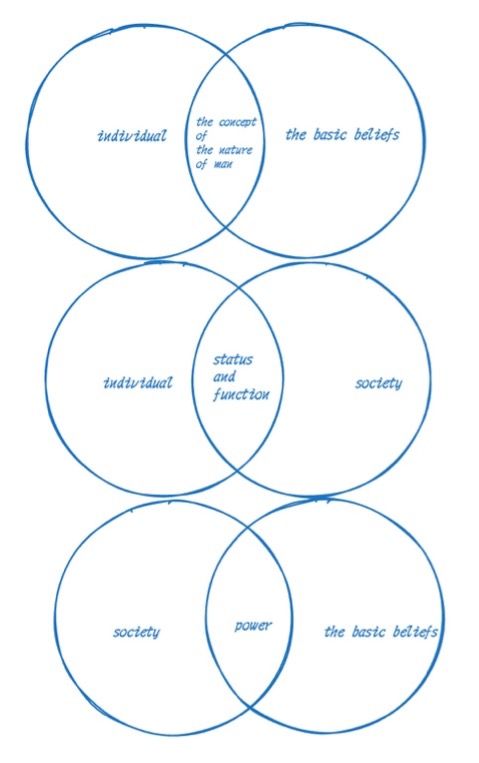

In The End of Economic Man, Drucker developed his diagnosis of totalitarianism around three issues: power legitimacy, individual status-function, and society's basic beliefs. In The Future of Industrial Man, he also constructs a general social theory around these three issues.

In "What Is A Functioning Society," Drucker explains three sets of tensions that exist in social ecology:

Tension between the individual and society's basic beliefs. "Society's basic beliefs" refer to two questions every society must answer: What is human? How should humans achieve fulfillment in life? Christianity provided answers to these questions, while Hinduism and Buddhism offered different answers. European society as a whole is a Christian civilization. Throughout its long history, Europeans' understanding of these two questions was shaped by Christianity. However, in different historical periods, Europeans sought their fulfillment in different social domains, leading to different "concepts of the nature of man" such as Spiritual Man, Intellectual Man, and Economic Man. Spiritual Man, Intellectual Man, and Economic Man all pursued the freedom and equality revealed by Christianity, but they sought these in entirely different domains. Thus, we have one set of tension: the tension between individuals and beliefs about human nature, with the "concept of human nature" serving as the mediator of this tension.

Tension between the individual and society, with individual status-function serving as the mediator of this tension. Traditional political philosophy often falls into debates between individualism and collectivism. Collectivism attempts to subtract the individual from society, while individualism attempts to subtract society from the individual. Drucker believes that if we use arithmetic language for analogy, the relationship between individual and society should not be subtraction but multiplication. When individuals have status-function, social life becomes meaningful. When society can bestow status-function upon individuals, it integrates social members and creates a meaningful social order.

Tension between society's basic beliefs and society itself, with power serving as the mediator of this tension. Any society needs to be organized according to specific beliefs. But beliefs alone cannot create society. What truly creates organization and order in society is power. It is real power that transforms lofty beliefs into concrete society.

The three sets of tensions interweave into a network. Within this network, each pole of tension must function for the other pole. The relationship between the two poles is a functional relationship. Their reason for existence is not themselves but the function they perform for external things. This is Drucker's basic approach to observing social ecology.

A functioning society can take many different forms because different societies uphold different beliefs. Christian societies and Hindu societies cannot be identical, but they can both be functioning societies. Regardless of how much societies differ in beliefs and appearances, a functioning society has essential elements:

Power must have legitimacy. For power to have legitimacy means that a society's dominant power (governmental power, social power) must commit to this society's basic beliefs and work according to these beliefs.

Society can bestow status-function upon individuals. Moreover, individuals' status-function aligns with society members' basic beliefs about human nature.

In a society, individuals have basic beliefs about "who am I" and "how should I exist."

A functioning society is not a "good" society or a "perfect" society. It has nothing to do with judgments like "good" or "perfect." As soon as we mention "good" or "perfect," we introduce specific value preferences. "What Is A Functioning Society" tells readers that, based on any value preference, it's possible to construct a functioning society or to make society paralyzed and disintegrate. A liberal who loves freedom, despite loving freedom, might be powerless to construct a functioning society because they cannot harness power or create visions for society and individuals.

"Free Society and Free Government" addresses how to construct a functioning free society based on belief in freedom.

Drucker's understanding of freedom belongs to the Christian tradition, not the 19th-century liberal tradition. He explains freedom from the perspective of the three sets of tensions:

Freedom exists in the tension between individuals and beliefs about human nature: "The only basis of freedom is the Christian concept of man's nature: imperfect, weak, a sinner, and dust destined unto dust; yet made in God's image and responsible for his actions." From this Christian expression of freedom, Drucker distills several elements of freedom: 1) Humans are imperfect and cannot be perfect; 2) Humans are God's creation and thus yearn for truth; 3) Humans must make choices because of their imperfection and must be responsible for their choices because they yearn for truth.

Freedom exists in the tension between individuals and society. Freedom is primarily a life experience of each individual, but individuals must live out freedom in social life. In social life, freedom is an organizational principle. Freedom as an organizational principle means allowing individuals to bear choice and responsibility. Where there is no choice, there is no freedom; where there is choice without accompanying responsibility, there is also no freedom.

Freedom exists in the tension between society and social beliefs. If a society has faith in the freedom revealed by Christianity, then the power of this society must use freedom as an organizational principle. Specifically, every society has two power centers: government power and social power. Therefore, free government and free society need to be discussed separately.

Elements of a free government: organized, legal, with defined power scope, responsible, and self-governing.

Elements of a free society: In society's constructive domains, people organize actions according to the principle of "choice-responsibility." Constructive social domains refer to different social areas where people project their beliefs about freedom in different societies. In some eras, people seek freedom in religious life; in others, they seek it in economic life. Those domains that allow people to place their beliefs in them and can inspire people's courage and creativity are constructive social domains. If a society's constructive domains are organized by freedom as a principle, we can say it is a free society.

The relationship between government power and social power: A free society should have a dualistic pattern of government and society. Government is a necessary condition for society's operation. But there must be a self-governing social domain to balance it. In the 19th century, this self-governing social domain was the market. In the 20th century, Drucker believed this self-governing social domain should be commercial enterprises and social organizations.

Drucker openly acknowledges that his understanding of free government and free society derives from the Christian tradition. In his view, one crisis of political thought is that people are often unaware of the origins of their political thinking. For instance, people frequently confuse the questions of "free government" and "best government." The inquiry into "free government" stems from Christianity, while the inquiry into "best government" comes from ancient Greece. The desire to find or create the "best government" is a long-standing impulse. This idea presupposes that humans can achieve perfection. If a perfect individual or a perfect group emerges, then the government run by them would be a "perfect government." Similarly, if a perfect individual or group proposes a perfect plan or system, then a government ruling according to this plan or system would be a "perfect government."

Even in the 20th century, even in freedom-loving America, people often forget that "free government" and "best government" are two different things. Those who love democracy frequently assert that democratic government is the "best government." Of course, followers of totalitarianism also assert that totalitarian government is the "best government." Drucker says the real danger is that any obsession with the "best government" will eventually lead to enslavement. This is because illusions such as "best," "perfect," or "ultimate" deprive citizens of choice and responsibility. Freedom, however, is precisely responsible choice.

In other chapters of The Future of Industrial Man, Drucker reveals two paths to defending freedom. One path: the conservatives of 1776, starting from Christian beliefs about the human heart, explored political and social innovations in Britain and America. The other path: 19th-century liberals believed that humans could achieve perfection through their own efforts; starting from their love of freedom, they walked the path of enslavement leading to totalitarianism.

General Social Theory and Drucker's Management Science

The social ecological perspective and understanding of freedom that Drucker demonstrated in The End of Economic Man and The Future of Industrial Man run through all his political and management writings.

Key themes in his work include:

Continuously tracking new social realities, identifying decisive social powers, and exploring how to give power legitimacy.

Defending the dualistic pattern of government power and social power. Studying changes in the nature of government, answering what it should do, can do, and cannot do. Studying how to organize society, building organizational theory, and exploring the legitimacy of organizational power.

Paying attention to the interaction between social beliefs and social reality, and the interaction among technology, population, and beliefs.

Caring about individuals' status and function within organizations.

Exploring how to apply freedom as an organizational principle to organizational structure design and work design.